The global crude oil landscape has entered a period of drastic structural transformation following the military intervention in Venezuela in early January 2026. This geopolitical shift, marked by the removal of the previous administration and the establishment of an interim government under U.S. influence, has fundamentally altered the supply-demand equilibrium for heavy-sour crude grades. As of January 2026, Brent crude prices have consolidated near the USD 60 per barrel mark, reflecting a delicate balance between immediate supply risks and the long-term prospect of millions of barrels returning to global markets.

Why Does Venezuela Matter So Much in Global Energy?

The answer lies beneath the surface.

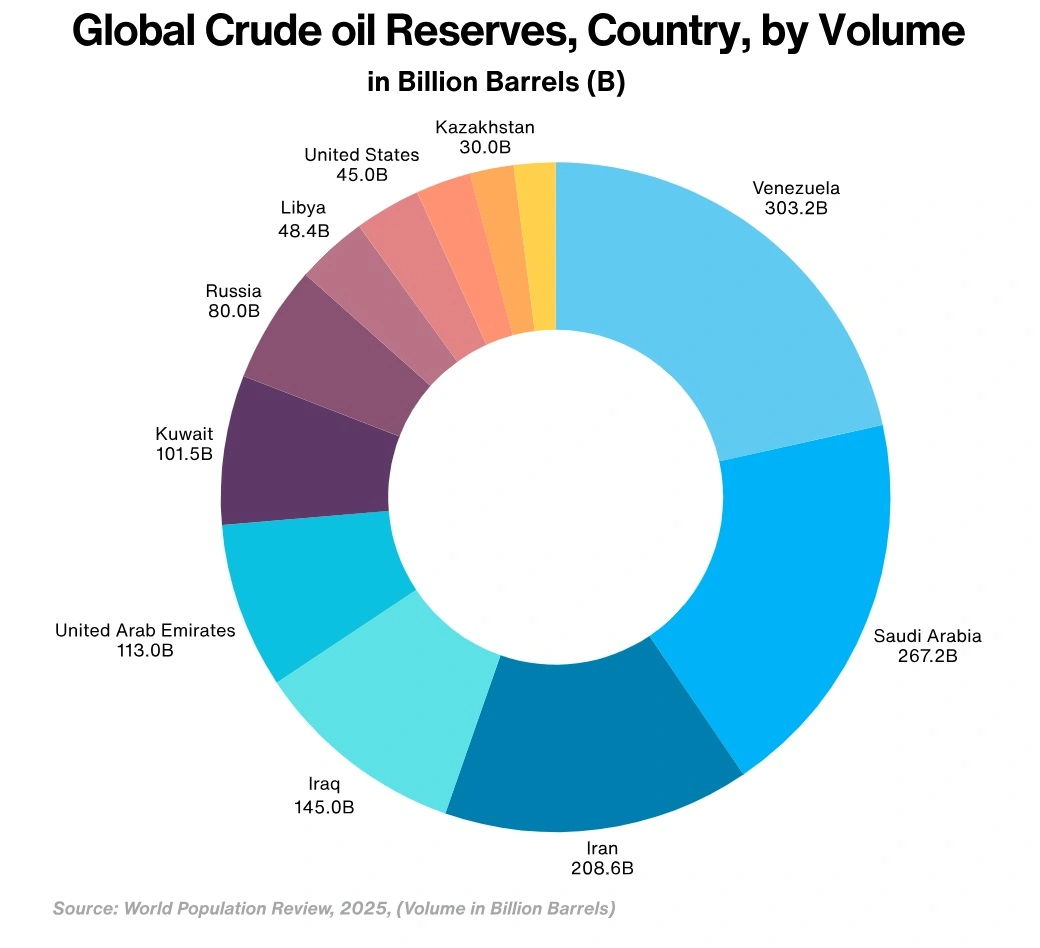

Venezuela possesses the world’s largest proven oil reserves, exceeding 300 billion barrels. This resource base dwarfs most other nations and represents a strategic energy prize that has shaped hemispheric politics for decades. To put this in perspective, Venezuela’s reserves exceed those of Saudi Arabia, making it theoretically the most oil-rich nation on Earth.

However, size isn’t everything. While the reserves are vast, the quality presents challenges. The majority of Venezuela’s oil is extra-heavy crude from the Orinoco Belt, which requires specialised refining infrastructure that only a handful of facilities worldwide possess. This combination of enormous reserves and technical complexity makes Venezuela uniquely important, not just as a source of supply, but as a critical feedstock for the world’s most sophisticated refineries. Control over these reserves means control over a significant portion of the heavy-sour crude market that powers global transportation fuels.

Why Is Venezuelan Oil So Difficult to Process?

Venezuelan crude is notoriously challenging due to its unique chemical composition. The vast majority of production is classified as extra-heavy or heavy-sour, characterised by high sulfur content and elevated levels of metals such as vanadium and nickel that can poison refinery catalysts. The primary export grade, Merey 16, has an API gravity of just 16.0 and sulfur content reaching 3.40%, with viscosity so high it requires heated storage and diluents for pipeline transport.

The high residue yield of Merey 16, exceeding 50%, makes it ideal for sophisticated coking units that can crack heavy molecules into valuable distillates like diesel and jet fuel. However, this same characteristic means simple refineries cannot process these barrels efficiently, effectively limiting the market to the world’s most advanced refining clusters on the U.S. Gulf Coast and in Asia.

| Grade | API Gravity | Sulfur (wt%) | Vanadium (ppm) | Viscosity @100°F (cSt) |

| Venezuelan Grades | ||||

| Merey 16 | 16 | 2.4-3.4 | 262-400 | 513 |

| Boscan | 10.1 | 5.4 | 1000-1200 | 11,233 |

| Bachaquero-13 | 12.2 | 2.8 | 442 | 48.6 |

| Mesa 30 | 30.5 | 0.85 | 38 | 7.29 |

| Furrial | 28.5 | 1.1 | 68 | 11.9 |

| Santa Barbara | 36 | 1.00 (est.) | – | – |

| Sweet Benchmarks | ||||

| WTI | 39.6 | 0.24 | Low | Low |

| Brent | 38 | 0.37-0.40 | Low | Low |

| OPEC Basket | ~32-34 | ~0.90-1.20 | Moderate | Moderate |

How Much Will It Cost to Fix Venezuela’s Oil Industry?

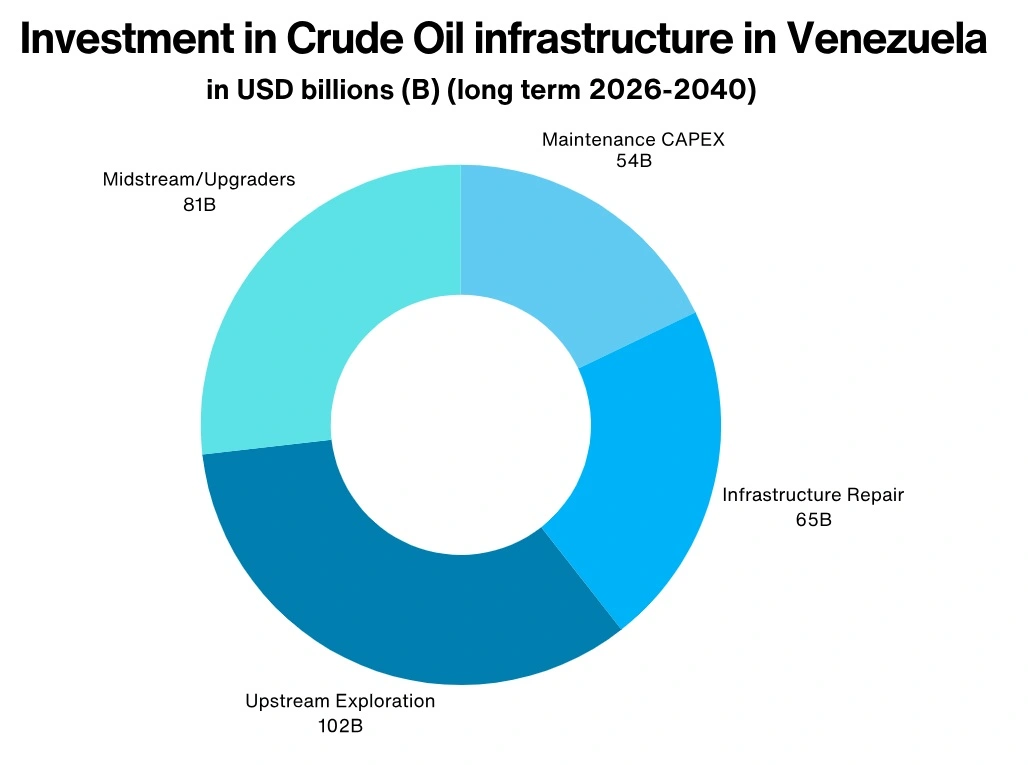

The answer is staggering: $183 billion between 2026 and 2040.

Decades of mismanagement, corruption, and lack of access to Western technology have left Venezuela’s energy infrastructure in structural collapse. The pipeline network, spanning 2,139 miles with theoretical capacity of 9 million barrels per day, averages over 50 years old and suffers from daily leaks and corrosion. Restoring this network alone requires $8 billion.

The situation is equally dire in upgrading facilities. Of the four major upgraders needed to convert extra-heavy crude into marketable blends, only the Chevron-linked Petropiar facility operates. Building a new upgrader costs tens of billions with a three-to-six-year lead time. Without functional upgraders, the industry relies on expensive imported naphtha and condensate as diluents, eroding profit margins.

The domestic refining sector has collapsed from nearly 1 million barrels per day in 2010 to just 250,000 bpd in 2025. The Paraguana Refining Center, once among the world’s largest, operates at roughly 10% capacity. Emergency repairs require an additional $10 billion investment.

Will Venezuela’s Recovery Be Quick or Slow?

History suggests patience is required.

Iraq and Libya provide sobering precedents. After the 2003 invasion, Iraq took nearly a decade for production to return to pre-war levels despite initial expectations of rapid recovery funded by oil revenues. Libya’s experience proved even more volatile, with production never consistently returning to prior levels since 2011 due to ongoing political instability.

| Historical Case | US Administration | Peak Decline | Recovery Duration | Relevance to Venezuela |

| Iraq (2003) | George W Bush (Republic) | 100% (Short-term) | ~8-10 Years | Infrastructure sabotage risk |

| Libya (2011) | Barack Obama (Democratic) | 90% (Periodic) | Incomplete (14+ yrs) | Fragmented political control |

| Venezuela (2026) | Donald J. Trump (Republic) | 68% (from 1970s) | TBD (Est. 8-15 yrs) | Long-term structural neglect |

For Venezuela, the “best-case” scenario assumes rapid political stabilization and immediate international investment, allowing production to normalize within three to five years. However, the more realistic “moderate” scenario incorporates periodic setbacks due to infrastructure failures and social unrest, extending the timeline to five or seven years. While the Trump administration claims $100 billion from U.S. oil companies could rapidly restore the sector, industry experts argue such timelines are unrealistic given the structural nature of the damage.

The consensus is that while sanctions relief could yield a short-term “bounce” of 300,000 to 500,000 bpd through well workovers, the long-term journey back to 2.5 million bpd requires fundamental restructuring of Venezuela’s fiscal and legal frameworks to attract sustained foreign capital.

What Happens to the 29 Million Barrels Already in Storage?

By early January 2026, Venezuelan floating storage reached a record 29 million barrels, driven by months of export restrictions and naval blockades. The U.S. administration plans to manage and sell between 30 and 50 million barrels of this seized or stored oil, providing immediate dollar inflows to interim authorities while easing supply tightness for heavy-sour crude on the U.S. Gulf Coast.

This “overhang” arrives amid a broader global oil surplus. The Energy Information Administration projects global production will exceed consumption by 2 million barrels per day in 2026, potentially filling land-based commercial storage to capacity. The International Energy Agency revised its 2026 surplus forecast to 3.84 million bpd, reflecting rising production in the U.S., Brazil, and Guyana alongside Venezuela’s potential return. This glut ensures that while Venezuela’s situation is transformational, it’s unlikely to trigger a price rally in an already saturated market.

Who Wins and Who Loses in the New Oil Order?

The biggest winners are U.S. Gulf Coast refiners.

Facilities from Corpus Christi to Pascagoula were specifically designed to handle corrosive, dense, high-sulfur grades. Complex refiners like Valero, Chevron, and PBF Energy can once again utilize their substantial coking and hydrocracking capacities to process discounted heavy barrels into high-value distillates.

| USGC Refiner | Key Facilities | Capability |

| Phillips 66 | Lake Charles, Sweeny | 100,000 – 200,000 bpd of heavy sour |

| Valero | Port Arthur, St. Charles | High coking capacity for Merey 16 |

| Chevron | Pascagoula | Proximity and historical partnership |

| PBF Energy | Chalmette | Strategic heavy feedstock souring |

Canadian producers face competitive displacement as USGC refiners pivot back to Venezuelan barrels. Western Canadian Select prices have already plunged to their largest discounts in 18 months, with spreads widening to over $14 per barrel. Canadian producers who successfully filled the gap left by sanctioned Venezuelan oil now confront a period of market share erosion.

Chinese independent “teapot” refiners, who capitalised on deeply discounted Venezuelan crude during the sanctions era, are forced to pay higher prices for alternative heavy grades from the Middle East or Russia. This has led to tightening of the Asian fuel oil market, with premiums for high-sulfur fuel oil doubling since early 2026.

What Does This Mean for Oil Prices in 2026?

The outlook remains bearish.

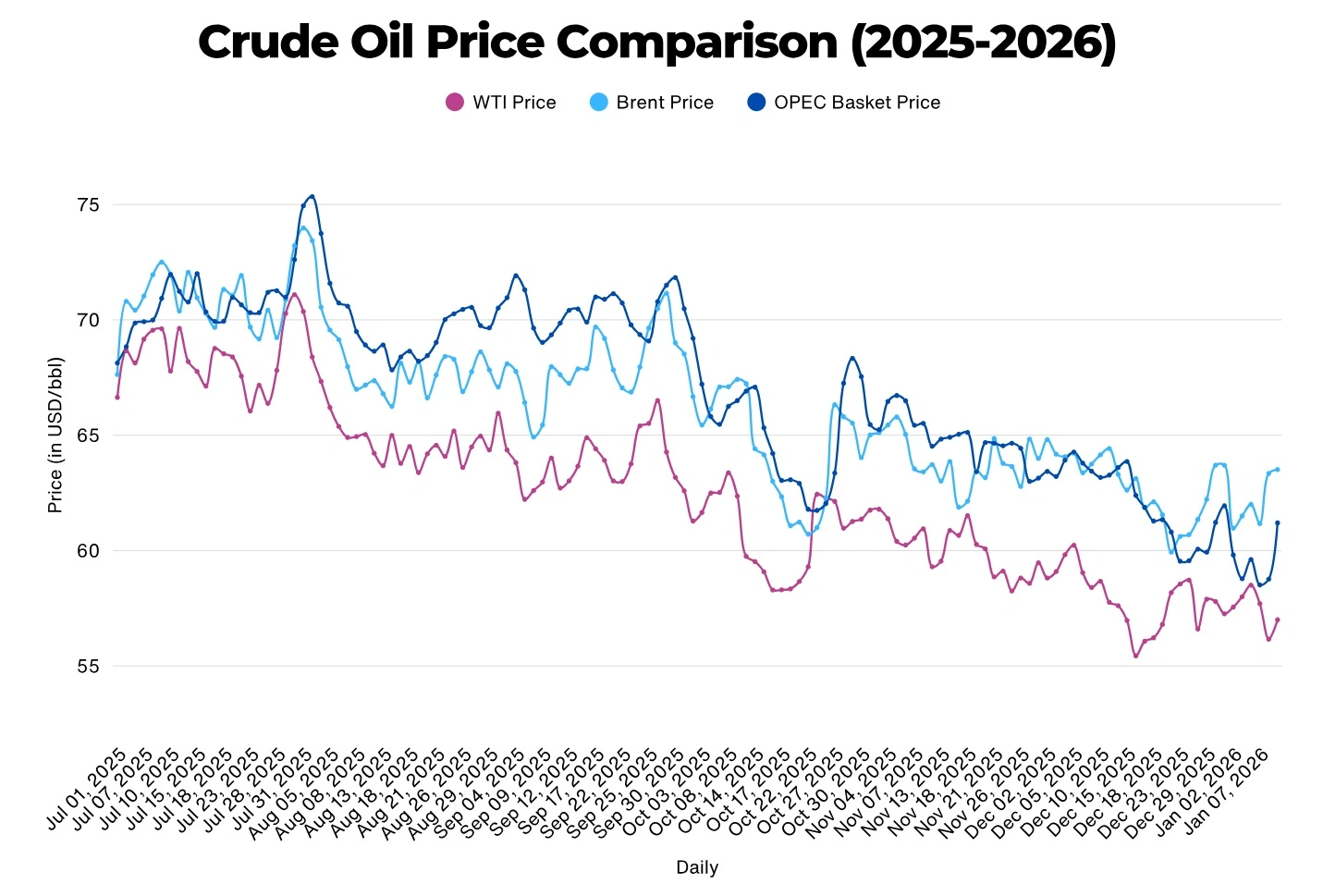

In 2025, crude oil prices experienced their steepest annual decline since the pandemic, with Brent and WTI falling approximately 20%. This downturn was driven by global oversupply as record U.S. output and OPEC+ production hikes outpaced sluggish demand. By year’s end, Brent settled near USD 61 per barrel.

The return of Venezuela ensures crude prices will remain capped in the USD 50-60 range throughout 2026, favouring the world’s most complex refiners and providing the U.S. administration with a powerful tool for regional energy security. Unless OPEC+ implements drastic production cuts or significant supply disruptions occur, 2026 is anticipated to be a year of continued price softening and market rebalancing.

Can OPEC+ Control Prices with Venezuela Back in Play?

The U.S. intervention introduces a new external actor into OPEC+ dynamics.

Venezuela, a founding OPEC member, has been diminished by years of underperformance and is currently exempt from production quotas. At the January 2026 ministerial meeting, OPEC+ reaffirmed steady production levels, adopting a “wait-and-see” approach.

The potential for U.S.-influenced Venezuela to surge production beyond 1 million bpd poses a threat to OPEC+ unity. If Venezuela is reintegrated into the quota system, it may spark tensions with members wary of market share erosion. Saudi Arabia and Russia may advocate for stricter compliance or revised baselines to accommodate returning Venezuelan volumes without derailing collective price targets. The question remains: does U.S. influence over Venezuela effectively give Washington a “seat at the table” in OPEC meetings?

Is the Global Oil Infrastructure Ready for This Shift?

Not even close.

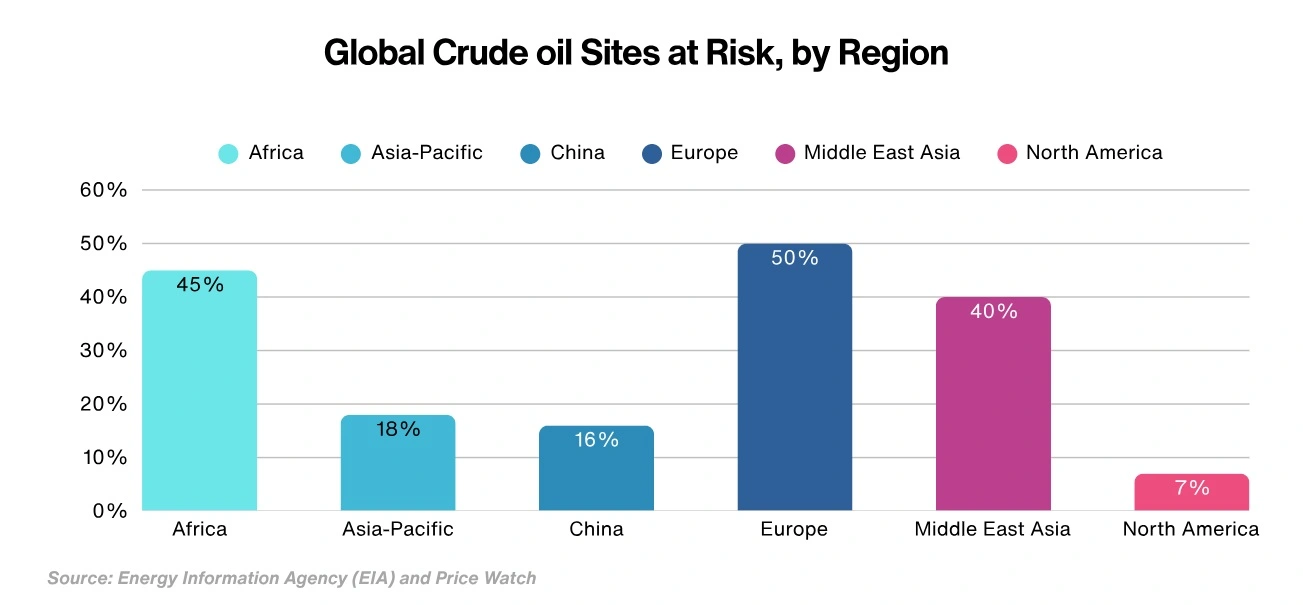

The global crude oil landscape reveals a sharp divide between aging Western infrastructure and fresh integrated complexes in the Global East and South. Approximately 21.6% of global refining capacity, representing 121 out of 465 screened sites, is classified as being on its “last legs” and at risk of closure by 2035. These vulnerable assets account for roughly 20.2 million barrels per day of processing power.

Europe holds around 50% of these at-risk sites. In the United States, the average crude distillation unit is 64 years old, with over 3 million bpd of capacity exceeding 90 years. Conversely, 5.8 million bpd of new capacity is projected by 2030, with 90% concentrated in Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. This infrastructure divergence supports the projected global oil surplus of 2-4 million bpd in 2026, keeping prices compressed despite high maintenance costs for legacy assets.

Geopolitical Stakes Extend Far Beyond Oil

The Venezuelan intervention has redrawn the power map of the Americas. Beyond energy security, the U.S. gains control over a strategic asset that has been a geopolitical thorn for decades. The liquidation of 30-50 million barrels of seized oil provides immediate revenue for the interim government while demonstrating American capability to reshape energy markets unilaterally.

For China, losing access to discounted Venezuelan crude represents a significant setback in its energy security strategy. For Russia, it’s another ally lost and another market disrupted. The intervention also sends a clear message to other resource-rich nations about the consequences of alignment against U.S. interests. The Venezuelan oil comeback is as much about geopolitical leverage as it is about barrels and prices.

The Venezuelan oil comeback represents one of the most significant supply shocks in modern petroleum history. While the resource base exceeds 300 billion barrels, the physical reality of 50-year-old pipelines, failing upgraders, and crumbling refineries will act as a permanent brake on production growth for the remainder of the decade. The “Venezuelan Renaissance,” while promising long-term, will serve primarily as a stabilizing force in an oversupplied global market in the near term, and as a powerful demonstration of American influence over global energy architecture.